How Galaxies Quench Star Formation Link to heading

Other Research Themes: How do galaxies like the Milky Way become what they are? | How do galaxies acquire their mass?

Overview Link to heading

One of the most fundamental puzzles in astrophysics is understanding why galaxies stop forming stars. Massive galaxies in the Universe today are “red and dead”—they contain trillions of stars but have virtually ceased star formation. The mechanism driving this quenching is galactic outflows: powerful winds driven by star formation and active galactic nuclei that transport gas and metals far from galaxies. By studying these outflows across cosmic time, we reveal how feedback regulates galaxy evolution and sets the fundamental properties of the galaxy population we observe today.

Why It Matters Link to heading

How exactly galaxies quench their star-formation is still less well understood part of galaxy evolution. Without feedback-driven outflows, galaxies would convert all their gas into stars, producing a galaxy too massive to exist. How a galaxy transitions from a star-forming state to a quiescent one depends critically on how effectively feedback can remove or heat gas, preventing it from cooling and forming new stars.

Galactic outflows also chemically enrich the circumgalactic and intergalactic media, distributing metals to vast distances and leaving imprints on the distribution and properties of gas throughout the Universe. Understanding outflows is therefore crucial for understanding not only galaxy evolution, but also the chemical enrichment of the Universe itself.

Our Approach Link to heading

We measure galactic outflows using high-resolution spectroscopy of absorption and emission lines at ultraviolet and optical wavelengths. By observing multiple metal ions at different ionization states, we can determine the temperature, density, velocity, and mass of outflowing gas across a range of physical conditions.

Additionally, we leverage gravitational lensing to study outflows in distant galaxies with unprecedented spatial resolution. Gravitational lensing amplifies the light of distant galaxies, allowing us to resolve outflows on scales of hundreds of parsecs—revealing the spatial structure and local properties of winds. High-resolution integral field spectroscopy from ground-based telescopes provides three-dimensional maps of emission-line kinematics, while ultraviolet spectroscopy traces hot and warm gas phases. Together, these techniques allow us to reconstruct the complete picture of how energy and momentum from star formation and black hole accretion are converted into outflowing gas.

Spatially-Resolved Outflows Revealed by Gravitational Lensing Link to heading

Traditional spectroscopy measures galaxy properties along a single line of sight, missing crucial spatial information about outflows. Gravitational lensing changes this paradigm by magnifying distant galaxies, effectively providing a natural “cosmic telescope” that resolves structures typically inaccessible through direct observation.

One of our key discoveries involved a gravitationally lensed star-forming galaxy at z = 1.70. Using deep IFU observations we map the small-scale variation of outflow kinematics across the galaxy, from parsec scales to kilo-parsec scales. We fidn that outflowing gas within the same galaxy can have velocities ranging from of -120 to -250 km/s. Remarkably, we found that the outflow properties were locally sourced—each clump of star formation drove its own localized wind, rather than a single coherent outflow. The mass loading factors were substantial, with several times the star formation rate being expelled as gas, meaning that 30-50% of the mass produced in star formation is immediately blown out.

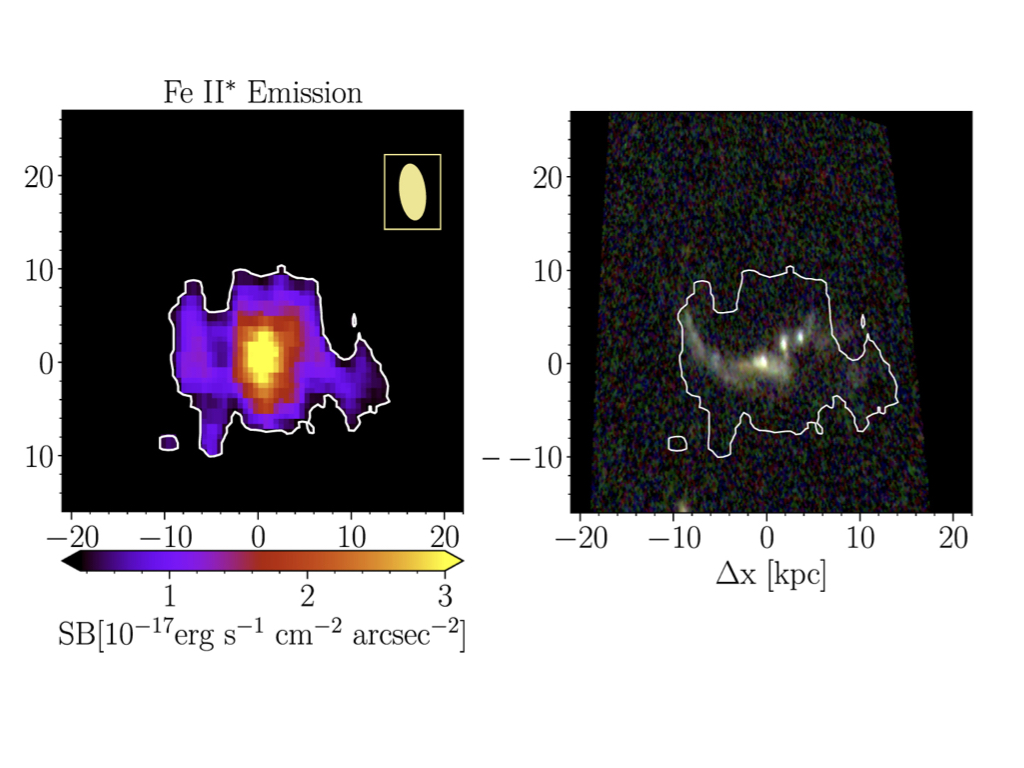

These outflows carry metals and energy into the circumgalactic medium, regulating future star formation. Around this galaxy, we use the spatially extended MgII and FeII* emission to map the spatial extent of the outflow, revealing an extended halo at least 30 kpc wide.

These observations demonstrate that outflows are not monolithic structures, but rather complex, patchy phenomena intimately connected to the underlying star formation distribution. Understanding this structure is crucial for interpreting outflows in less-magnified galaxies and for building more realistic simulations of galaxy evolution.

Multi-Phase Outflows: From Cool Gas to Hot Winds Link to heading

Galactic outflows exist in multiple temperature phases, each tracing different physical processes. Cool gas (traced by low-ionization species like MgII and FeII) originates from disrupted interstellar material. Warm gas (traced by moderately ionized species) represents transitional phases where gas is being shock-heated. Hot gas (traced by O VI and other highly ionized ions) carries the energy and momentum of energetic feedback processes.

Our studies reveal a complex picture: low-ionization gas dominates at low outflow velocities, while highly ionized gas becomes increasingly important at high velocities where it can escape the galaxy entirely. This suggests that the most effective channel for removing gas from galaxies is through the hot phase, where gas has sufficient energy to overcome the gravitational potential.

Dependence on Galaxy Properties Link to heading

The strength and properties of galactic outflows depend sensitively on galaxy characteristics:

Stellar mass: More massive galaxies drive more energetic outflows, with higher velocities and larger mass loading factors.

Star formation rate surface density: The intensity of outflow scales with the star formation surface density, showing that feedback strength increases with the vigor of star formation.

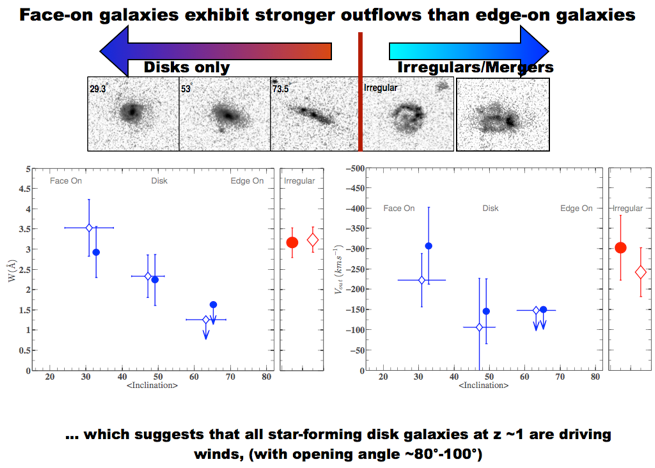

Galaxy morphology and orientation: Disk-dominated galaxies show bipolar outflow geometries aligned with the disk rotation axis, while face-on disks exhibit higher outflow velocities than edge-on systems.

Galaxy color: Blue, star-forming galaxies exhibit stronger outflows than red, quiescent galaxies, consistent with outflows being driven by star formation itself.

These dependencies reveal the physical connection between star formation and feedback: the most vigorously star-forming galaxies produce the strongest outflows, which in turn suppress further star formation, leading to galaxy quenching.

Key Results & Publications Link to heading

Dissecting a 30 kpc Galactic Outflow at z~1.7 Deep integral field spectroscopy reveals a spatially extended outflow across 30 kpc with highly clumpy and asymmetric morphology. The outflow exhibits complex kinematics with multiple velocity components, indicating that feedback-driven winds remain structured and spatially resolved even at large distances from the galaxy. Shaban et al. 2023

A 30 kpc Spatially Extended Clumpy and Asymmetric Galactic Outflow at z~1.7 Multi-wavelength observations reveal a giant outflow extending to 30 kpc with clumpy morphology and significant asymmetries. The study demonstrates that galactic outflows are not smooth, uniform structures, but rather complex, turbulent phenomena shaped by the underlying star formation distribution and interactions with the circumgalactic medium. Shaban et al. 2022

Spatially Resolved Galactic Wind in Lensed Galaxy RCSGA 032727-132609 We resolve outflowing gas across 6 kpc in a z=1.70 lensed starburst using MgII and FeII tracers. Outflow velocities reach -170 to -250 km/s with mass loading factors of several times the star formation rate. Remarkably, the outflow is locally sourced, with star formation clumps driving their own winds. Bordoloi et al. 2016

Feeding the Fire: Tracing Mass-Loading of 10⁷ K Galactic Outflows with O VI Absorption Multi-phase analysis of a z~2.9 lensed galaxy reveals that highly ionized gas (O VI) dominates the high-velocity outflow, suggesting that hot gas is the primary escape channel for removing gas from galaxies. Chisholm et al. 2017

The Dependence of Galactic Outflows on the Properties and Orientation of zCOSMOS Galaxies at z ~ 1 Analysis of 486 galaxies at z~1 reveals that outflow strength correlates with stellar mass, star formation rate, and star formation surface density. Disk-dominated galaxies show bipolar outflow geometries, while face-on systems exhibit higher velocities than edge-on ones. Bordoloi et al. 2014

The Team Link to heading

This research involves collaborations across multiple institutions, bringing together expertise in spectroscopy, gravitational lensing, and galaxy evolution. Graduate and undergraduate students contribute significantly to observational campaigns and data analysis.

Related Resources Link to heading

- Circumgalactic Medium Research Page — Gas enriched and transported by outflows

- Main Research Overview — Summary of all research areas